The poorest New Yorkers lived in these shacks

By the end of the 19th century, two-thirds of New Yorkers lived in dark, crowded tenement houses—the city’s answer to the housing needs of the working-class and poor.

As bad as some tenements could be, they may have been a step up from the shacks that some city residents called home until the turn of the century and even beyond.

Some of these broken-down dwellings were crammed behind newer tenements downtown, others were patched together with scraps of wood and other materials and located in uptown areas that were transitioning from farmland to part of the urban city.

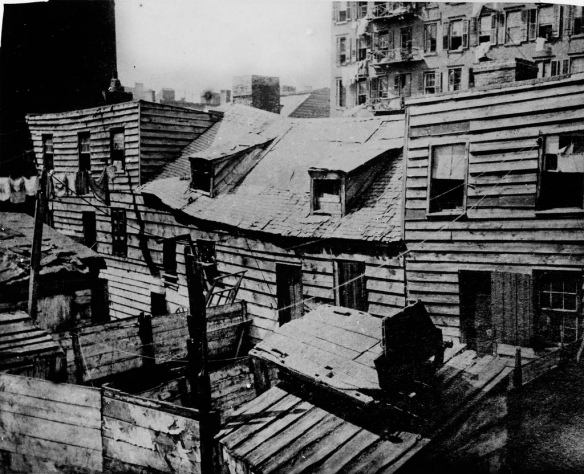

Jacob Riis took the first photos in this post. Riis was the journalist turned social crusader who wrote How the Other Half Lives in 1890.

He took the top photo in 1872, of what he called a “den of death,” for the Board of Health. It was at Mulberry Bend, part of the infamous Five Points neighborhood.

In 1896, he took the second photo, a shack in an unnamed neighborhood. All we know is that is was part of a shantytown with new tenements rising eerily beside it.

The third image is another dwelling in this shantytown, with a family posing amid what looks like laundry lines.

Riis took the photo, as well as the fourth shot, from 1890, of a rundown home between Mercer and Greene Streets in what would not be a choice neighborhood at the time.

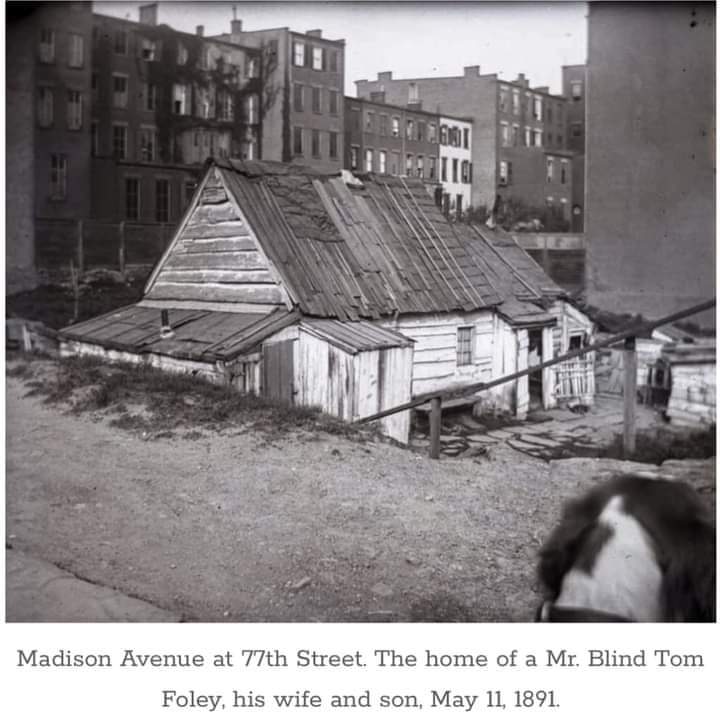

Madison Avenue and 77th Street is pretty luxe these days. In 1891, a man named Blind Tom Foley lived in this shack there with his family.

In 1910, Amsterdam Avenue had its hardscrabble sections, as this photo of a group of shacks there shows.

The final photo was taken in 1894 and gives us Fifth Avenue at 101st Street. Not far from where Andrew Carnegie’s massive mansion would rise, New Yorkers lived in these hovels, the riches of the Gilded Age no where in sight.

[Photos: Museum of the City of New York digital collection]

A ship captain built this 1830 Allen Street house

In the early 19th century, the city of New York was booming and expanding.

Eyeing undeveloped land on the east side of the Bowery, city officials issued a proclamation in 1803 that ordered “all the streets on the ground commonly known by the name of ‘De Lancey’s ground’ be opened as soon as possible.”

‘De Lancey’s ground’ was a 300-acre estate on today’s Lower East Side (and the namesake of Delancey Street, of course.)

The land was once owned by James De Lancey, a prominent New Yorker of French Huguenot descent who sided with the British during the Revolutionary War and subsequently had his land seized by the city.

Within a few decades of the city order, roads, building lots, and then houses went up on the former De Lancey estate. By the 1820s, the area was filling up with tidy 2- and 3-story homes.

One of these homes was the Federal-style house at 143 Allen Street, built in 1830 and a rare survivor of this early 1800s building boom.

Number 143 and five others just like it were developed by George Sutton, a ship captain who sailed between New York and Charleston along what was called the “Cotton Triangle.”

Like so many other New Yorkers, Sutton made his money off Southern cotton.

His ships would bring cotton picked by slaves on plantations to Manhattan, where it would be transferred to ships heading to England, according to a Landmarks Preservation Commission report.

“The six houses at Allen and Rivington Streets were maintained as investment properties, although Sutton seems to have preferred renting the buildings to friends and business associates—many of whom also participated in the Cotton Triangle trade,” states the LPC report.

Perhaps realizing that middle and upper class New Yorkers were now moving into fashionable neighborhoods north of Houston Street, Sutton sold the Allen Street houses by 1838.

As early as the 1840s, Number 143 was chopped into a multi-family dwelling. Over the decades the occupants reflected waves of immigration, from a Prussian family of eight in the 19th century to 15 tenants, mostly salesmen, in the early 20th century.

Number 143’s stoop was removed at some point in the 1900s—but so were the elevated train tracks that since 1879 had cast Allen Street in darkness (in the above left photo, you can just see the house’s dormers peeking out above the tracks).

A group of artists bought 143 and its surviving sister house, 141, in 1980 (the above photo shows the two homes in 1985.) Number 141 was eventually sold and demolished.