The severity of the extraordinary winter of 1917–1918 in the United States remains an important but relatively unexplored chapter of the First World War. Beginning in December 1917, and continuing through January and February of 1918, a powerful series of unrelenting and formidable ice storms and blizzards wreaked havoc across the nation, reaching from as far west as Omaha, Nebraska, and as far southwest as Memphis, Tennessee, to the port cities of the Atlantic Seaboard, and as far south as Norfolk, Virginia. This unprecedented winter onslaught caused civilian food and coal shortages in some northeastern states, coupled with the simultaneous inability to send critical logistical support to the Allied war effort on the Western Front. In particular, the storms paralyzed New York Harbor, the logistical center for support for the war in Europe in the eastern US. A useful historiographic framework for understanding the winter storms that incapacitated New York Harbor is Lisa Brady’s analysis of acoustical shadows, which conceptualize meteorological phenomena as both historical actors possessing agency and also as an extension of Clausewitz’s concept of nature as friction to understand the relationship between war and the environment.

The blizzards and subzero conditions stretching from the Midwest to the Eastern Seaboard struck when the American transportation system was already in disarray and on the verge of complete collapse because of freight car shortages, a national coal shortage, and the mismanagement of east-west rail-freight traffic. In short, the national rail systems simply could not handle the unprecedented flow of food, munitions, and supplies into East Coast ports. On 1 November 1916, railroads experienced a shortage of 115,000 empty freight cars of various types. Only three months later, in February 1917, 145,000 freight cars accumulated at eastern points producing increased congestion that became self-reinforcing and ultimately led to paralysis across the entire national transportation system. Some rolling stock stayed put because of various “competing” railroads’ reluctance to ship empty—and therefore revenue free—freight cars back to their point of origin while other cars simply became trapped in gridlocked yards and on industrial sidings. Once the storms arrived freight cars became frozen in place, which trapped others behind them, eventually bringing the system to a standstill.

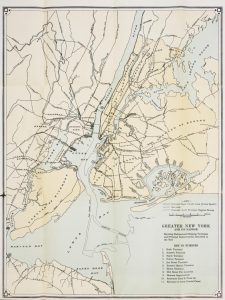

The railroads and docks of Manhattan were especially susceptible to ice as New York Harbor was primarily a lighterage port and relied on a system of car floats, barges, and lighters—small ships that transferred small amounts of cargo from land to water or from ship to ship—to move freight or coal to ships across the harbor or moored in the various rivers and inlets surroundings the metropolitan area. The absence of large dockside cranes, standard to harbors across the rest of the world, made Manhattan unique, as did the absence of any tunnels or bridges allowing freight trains to directly enter Manhattan from New Jersey and points south, an infrastructure problem that continues to exasperate policy experts today. (See Figure 1) An editorial entitled “The Real Tug of War” in the 26 October 1917 edition of Railway Age Gazette predicted the possible collapse of operations on the Eastern Seaboard due to the combination bad weather and infrastructure deficiencies, a viewpoint similar to testimony given by the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad before the Interstate Commerce Commission in March 1917.

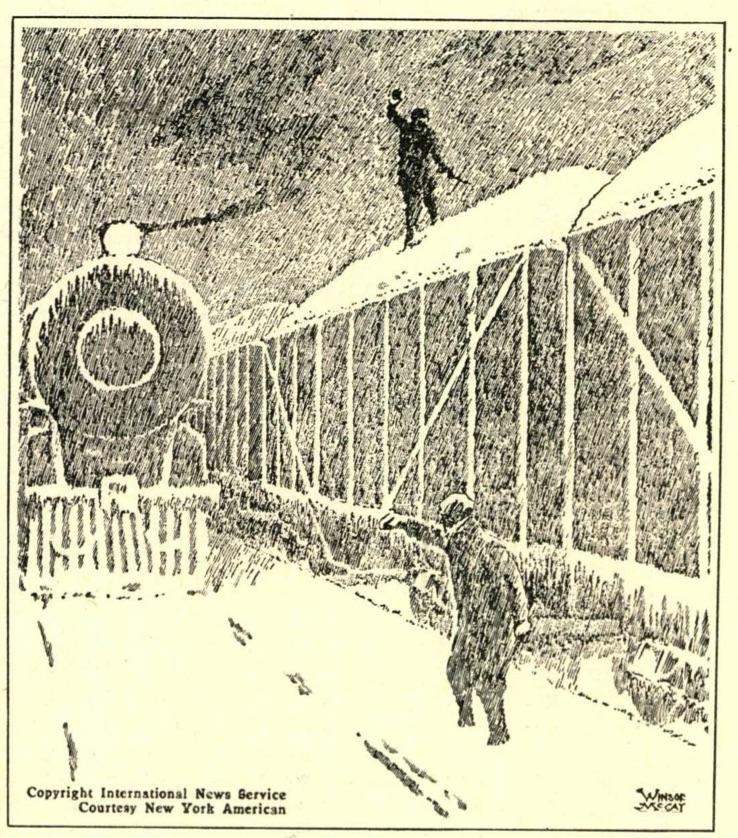

Once the Hudson River became choked with ice, it became impossible for lighters and barges to coal ships that lay at anchor, and the merchant fleet soon became as immobile as the surrounding rail yards. In time, the movement of railroad rolling stock by car-floats, barges, and the transfer of coal to barges between New Jersey, Staten Island/Port of Richmond, Brooklyn, and New York City completely stopped (see Figure 3). As the storms continued, paralysis on both land and sea made the loading of cargo for the Western Front all but impossible. In addition, coal from southern mines was also unable to reach New England cities. Dr. Harry A. Garfield, the leader of the US Fuel Administration, explained the situation as follows: “At tidewater the flood of freight has stopped. The ships were unable to complete the journey from our factories to the war-depots behind the firing line … The wheels were chocked and stopped, zero weather and snow bound trains; terminals congested; harbors with shipping frozen in; rivers and canals impassable …” (Railway Age, 199.)

In response to these conditions, President Woodrow Wilson nationalized American railroads and various riverine and coastal transportation systems on 26 December 1917 using the Army Appropriations Act of 1916. Wilson appointed William McAdoo, the first Director General of the Railroads, two days later, and McAdoo quickly found himself and the national transportation system unprepared for three months of historic winter storm systems. McAdoo noted: “The harbors on the Eastern Seaboard were crowded with ships that could not depart … on account of a lack of coal … the coal could not be brought to the ports because of the congestion on the railroads. Things were moving in a vicious circle.” (457) The simultaneous collapse of both rail and river freight movement temporarily brought the harbor to a standstill.

In early spring, as the weather stabilized, strict military mobilization timetables were reestablished but not before convincing transportation leaders that the lifeline to the Western Front was susceptible to breakdown due to infrastructure weaknesses. Events in New York Harbor illustrate the power of weather to stymie large technological systems and the usefulness of examining a military-logistics crisis through an environmental lens